History of Rope Dart and Meteor Hammer

The rope dart (sheng biao) and meteor hammer (liu xing chui) are traditional Chinese flexible weapons with rich histories rooted in ancient martial arts and performance traditions.

The meteor hammer is believed to have originated as a hunting tool similar to the South American bolas, featuring weights connected by a rope designed to entangle prey. Over time, it evolved into a weapon consisting of one or two weighted heads attached to a flexible chain or rope. Its design allowed for concealment and versatility in combat, enabling practitioners to strike from a distance or ensnare opponents.

The rope dart, closely related to the meteor hammer, features a metal dart attached to a long rope. Its first documented appearance dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), where it was utilized as a hidden weapon due to its compact size and ease of concealment. Primarily employed as a last-resort weapon, the rope dart allowed warriors to maintain distance from adversaries while delivering precise strikes.

Rope dart and meteor hammer are two traditional Chinese flexible rope weapons known for their stealth and striking range. The rope dart (绳镖 shéng biāo) consists of a long rope (typically 3–5 m) with a metal dart or blade attached at one end. The meteor hammer (流星锤 liúxīng chuí) features one or two heavy weights attached to a rope or chain. Both weapons belong to the “soft” weapons category in Chinese martial arts and rely on momentum and skilled manipulation. Below is a detailed history of each, including their origins, cultural roles, evolution in martial arts, military value, modern usage, and notable historical references.

Origins and Early History

Rope Dart

The rope dart’s origins can be traced back over a millennium. The first written description of a rope dart dates to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD). Some sources even suggest it may have been in use as early as the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 24 AD), though solid evidence from that era is scarce.

In its earliest form, the rope dart was likely a concealable projectile weapon—essentially a dagger or spike attached to a cord. Its compact size and flexibility made it easy to hide, which is why ancient soldiers reportedly carried it as a “hidden weapon” for emergencies. If a warrior lost or exhausted their primary weapons (spear, sword, bow, etc.), a rope dart could be deployed as a last-resort surprise weapon. Despite these early mentions, concrete artifacts of rope darts are rare. The weapon may not have been distinguished from other rope-based arms in early records.

In fact, the rope dart as a distinct weapon (separate from similar tools like the meteor hammer or flying claw) is not clearly depicted in art until the 19th century. A drawing in a 19th-century Beijing street vendor book is the earliest known explicit illustration of a rope dart. Early art (along with early 20th-century photographs) suggests rope darts were used by street performers, often featuring bamboo tubes as sliding handles for trick routines. Thus, while the rope dart’s conceptual origins are ancient, its recognition as a unique weapon came much later in history.

Meteor Hammer

The meteor hammer has an even older pedigree. Archaeological finds show that weighted rope weapons existed in China by the Warring States period (475–221 BC).

For example, a bronze meteor hammer head from the Ordos region, attributed to nomadic Xiongnu culture, dates to this era. This indicates that the idea of swinging a weight on a rope to strike or entangle has been part of Chinese weaponry for over two millennia. Some historians liken early meteor hammers to a form of sling that isn’t released—essentially a weight hurled while still attached to a cord. These could have been used for hunting or combat, especially from horseback, since the wielder could retrieve the weight after throwing.

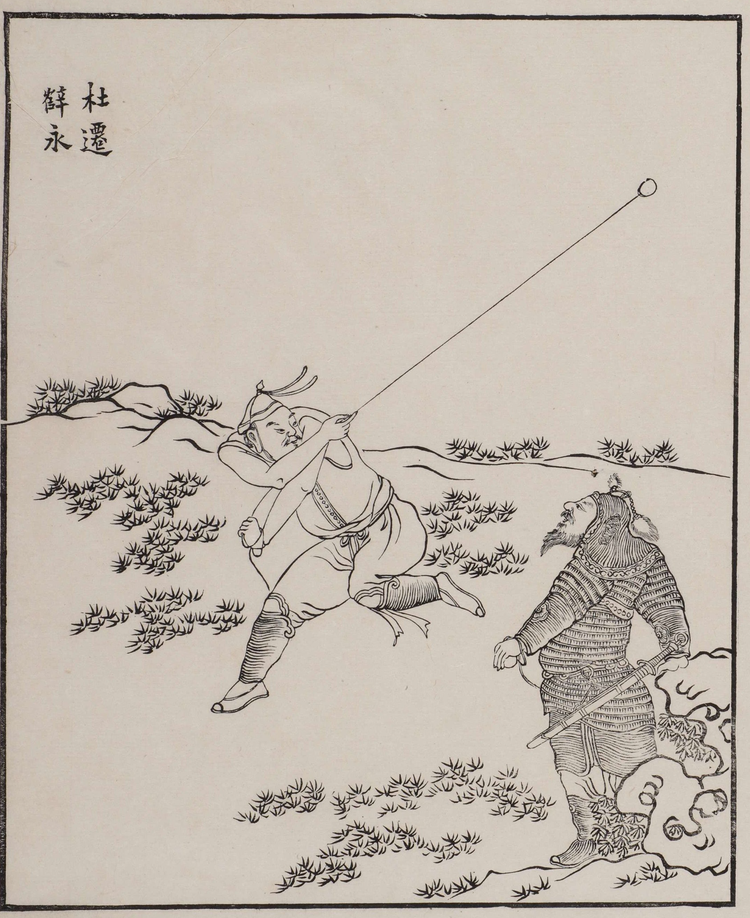

By the late imperial period, the meteor hammer was well known in martial culture. It appears in Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) military encyclopedias under various names. The San Cai Tu Hui (1609), a comprehensive Ming encyclopedia, lists a “Star Hammer” (星鎚) among flexible weapons. Surviving illustrations from such texts depict metal weights (often melon- or bullet-shaped) attached to long cords.

Multiple terms existed for the meteor hammer; for instance, a military manual refers to a spiked variant as lián chuí (链锤, “chain hammer”). Unlike the rope dart, the meteor hammer was clearly recognized in Chinese records by the late medieval period. Assorted ancient bronze weights used for meteor hammers from the Jin–Yuan dynasty era suggest that these heads were attached to long ropes or chains, forming meteor hammer weapons still recognizable in martial traditions today.

Cultural Significance in Chinese History

Throughout Chinese history, flexible weapons like the rope dart and meteor hammer occupied a unique space between combat, performance, and folklore. Unlike swords or spears, these weapons never became standard tools of war, yet they carried an air of mystery and skill that made them enduring symbols in martial arts traditions, street performances, and Chinese literature. Their ability to be concealed, their unpredictable motion, and the sheer dexterity required to wield them gave them a legendary status among martial artists, entertainers, and storytellers alike.

As China’s martial traditions intertwined with street entertainment, the rope dart and meteor hammer found a new home in performance art. By the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), street performers had turned these once-hidden weapons into mesmerizing displays of speed and dexterity. Historical records, including 19th-century Beijing illustrations, depict entertainers using these weapons to dazzle audiences with spinning feats, incorporating wraps, releases, and lightning-fast strikes to create an illusion of effortless control.

The performative nature of these weapons extended into folklore and classical literature. While they were rarely mentioned outright, many martial legends describe warriors using “flying daggers attached to cords” or weighted chains to snare enemies, disarm foes, or even ensnare spirits. One of the most famous literary appearances comes from the 14th-century novel Water Margin (Outlaws of the Marsh), where the bandit-hero Xue Yong demonstrates meteor hammer techniques as a street performer before joining a legendary group of outlaws. His portrayal as a skilled but unorthodox fighter reflected the weapon’s growing association with those who lived outside the rigid codes of conventional martial society. Another character, Fan Rui, wielded a fearsome variation known as the “Dark Meteor Hammer” (暗黑流星锤, àn hēi liúxīng chuí), further embedding the weapon in folklore as something both mysterious and deadly.

Beyond literature, martial opera troupes often included rope dart and meteor hammer techniques in their performances, reinforcing their place in the mythology of wandering swordsmen and righteous outlaws. Legends tell of warriors who used these weapons to bind enemies alive rather than kill them, a theme that reinforced the idea of skill and intelligence triumphing over brute force. Some stories even suggested that these weapons could be used to disarm supernatural threats, adding a mystical element to their legacy.

Today, the rope dart and meteor hammer continue to captivate martial artists, historians, and fans of Chinese cinema. They remain a staple of wuxia (martial hero) novels, period dramas, and kung fu demonstrations, instantly evoking a sense of archaic skill and mastery. While no longer practical weapons, they are still respected as a test of coordination and reflexes, and their historical connection to both combat and performance ensures their continued presence in martial arts traditions.

Whether as hidden weapons, instruments of theatrical spectacle, or legendary tools of outlaws and heroes, the rope dart and meteor hammer have left an indelible mark on Chinese culture, symbolizing not just combat proficiency, but the fine line between martial discipline, artistry, and myth.

Evolution in Martial Arts Practice

The rope dart and meteor hammer evolved from simple flexible weapons into sophisticated tools of combat, performance, and martial arts discipline. Though they were never standard battlefield weapons, their fluid, rapid motion and adaptability made them highly respected in traditional kung fu schools, Shaolin training, and modern Wushu demonstrations. Their techniques were passed down through generations, with some schools preserving their combat applications while others adapted them for performance art and competitive martial arts.

Techniques and Training

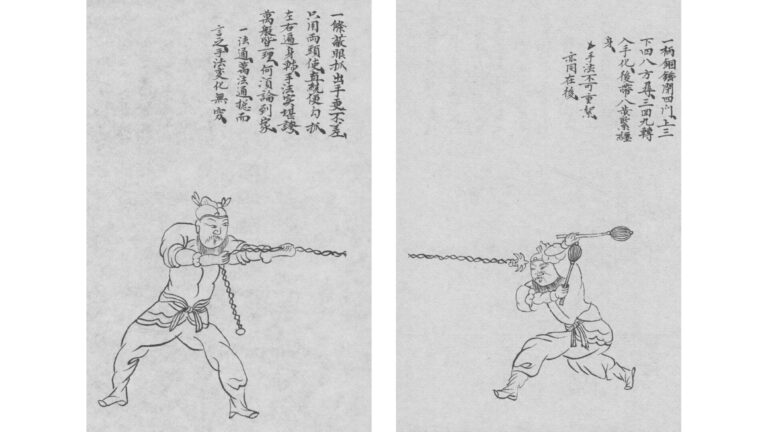

Both weapons require exceptional dexterity, precise timing, and full-body coordination. Manuals from the 18th and 19th centuries illustrate the refined use of flexible weapons like the rope dart, and some even include the meteor hammer’s swinging and wrapping techniques. The Shaolin Yǐbō Zhēnchuán, a Praying Mantis Fist manual, contains diagrams of rope dart techniques, suggesting that by the Qing Dynasty, some Northern Praying Mantis schools had formally incorporated the weapon into their curriculum. Practitioners learned to shoot the dart or weight out suddenly and retract it seamlessly, allowing for unpredictable strikes from multiple angles and distances.

Movements for both weapons often involve wrapping the rope or chain around the body—the neck, arms, legs, or torso—to generate momentum before launching the weapon in a straight-line attack or looping snare. This method enabled skilled users to strike from unexpected positions, entangle an opponent’s limbs or weapon, and transition between offensive and defensive movements fluidly.

Certain martial arts schools became known for flexible weapons training, particularly those linked to Shaolin and Wudang traditions. The Shaolin Monastery, famous for its extensive weaponry training, later incorporated the rope dart and meteor hammer into its curriculum. Other styles, such as Wudangquan, which emphasized internal energy and flowing movements, also made use of these weapons. However, due to their difficulty, these techniques were typically reserved for advanced students, ensuring that only those with strong foundational martial skills could wield them effectively.

Martial Evolution and Modern Adaptations

Unlike more common weapons like the staff or straight sword, flexible weapons like the rope dart and meteor hammer were not universally taught. Their high skill ceiling and potential for self-injury limited their adoption in mainstream martial arts. However, within specific kung fu lineages, they became hallmarks of elite training, with some styles featuring a single master or lineage holder responsible for passing down these techniques.

By the 20th century, these weapons saw a resurgence, particularly through modern Wushu, which adapted traditional techniques for competitive and performance-based martial arts. Wushu athletes typically train with the chain whip before advancing to the rope dart, ensuring they develop the necessary agility, spatial awareness, and control. Unlike their battlefield counterparts, modern Wushu versions of the meteor hammer and rope dart are often made of lighter materials, allowing for dazzling, high-speed performances without the risks of heavier versions.

The meteor hammer, which had once been a tool of both combat and entertainment, remained rarer in formal martial arts competitions. However, its blindingly fast whirls, unpredictable strikes, and ability to entangle opponents made it a favorite in traditional kung fu circles and stage performances. Historical records from the late Ming period even depict warriors using the meteor hammer on horseback, showcasing its effectiveness in combat.

The Legacy of Flexible Weapons in Martial Arts

While both weapons have evolved far from their original combat applications, they remain symbols of martial skill and ingenuity. In recent years, international martial artists and flow arts practitioners have begun to blend traditional rope dart and meteor hammer techniques with modern movement arts, further pushing the boundaries of what these weapons can do.

From Shaolin temple courtyards to global Wushu arenas, the rope dart and meteor hammer continue to captivate audiences and challenge martial artists, ensuring that these ancient weapons remain relevant in both historical martial traditions and contemporary performance arts.

Military Applications and Combat Effectiveness

Historical Battlefield Use

Both the rope dart and meteor hammer have an undeniably cool factor, but were they practical in actual warfare? Historical evidence suggests their battlefield use was limited. Standard armies of ancient China favored spears, swords, bows, crossbows, and later firearms—weapons that were easier to train with and more reliably lethal. Flexible rope weapons like the meteor hammer likely saw occasional use in specific scenarios rather than as common armaments. In fact, historians note there is little evidence of meteor hammers being widely used in real combat. Their effectiveness was constrained by open space requirements and the high skill needed to avoid entangling oneself. A swordsman or spearman with moderate training could often dispatch a meteor hammer wielder unless the latter was exceptionally skilled or had room to maneuver.

Nonetheless, Chinese military texts did acknowledge these weapons. The comprehensive Ming military treatise Wubei Zhi (1621) included entries on flexible chain weapons. One section describes special rope/chain weapons intended to entangle cavalry or pull riders off horses—essentially weighted ropes or claws thrown at mounted troops. In the same text, a diagram shows a double-headed meteor hammer alongside other arms, indicating the concept was known to military strategists. Another military manual from the early 17th century lists the meteor hammer (with spikes added) among its arsenal, implying it was theoretically considered for combat. These inclusions suggest that while not mainstream, meteor hammers were thought of as niche tools for specific purposes like disrupting cavalry or capturing foes. The rope dart, being lighter and bladed, might have been viewed similarly as a tool for ambush or pursuit—a way to injure or slow an enemy fleeing at a distance. However, formal military documentation of the rope dart is scant compared to the meteor hammer. It likely fell under the broad category of fei tou (飞头, “flying weight”) or other general terms in manuals.

In one intriguing account, late Ming era illustrations (possibly in the manual Kang Ji Pu) depict a scene of a soldier inside a siege tower wielding a meteor hammer. This suggests a defensive role: swinging the hammer from atop fortifications to strike besiegers below or to protect a fixed position. Still, these examples appear to be more theoretical or limited in scope. By and large, rope darts and meteor hammers were auxiliary weapons, used by guards, outlaws, or as a last resort rather than issued to regular troops. They required too much open space and specialization, whereas polearms and bows were more straightforward on the battlefield.

Combat Effectiveness

When used by a trained expert, both weapons could be formidable in one-on-one combat or skirmishes. The rope dart’s strength lay in surprise and reach – an enemy could be engaged from several meters away with a sudden dart strike or tripping maneuver. It could pierce vulnerable spots in armor or, with a wrap technique, even tie up an opponent’s limbs. The meteor hammer delivered concussive force; a solid hit from the swinging weight could crush bones or knock a helmet askew. It was also useful for entangling weapons: whipping the rope around an enemy’s spear or sword to disarm them.

However, these benefits came with drawbacks. Both weapons were almost useless in tight formations or cramped environments. A swinger needed room to arc the weight; in a dense melee, this was impractical. Moreover, a missed throw could leave the wielder momentarily vulnerable while retracting the weapon.

Historical consensus is that these rope weapons were more effective in duels, ambushes, or as specialist weapons than in mass combat. They might have been employed by bodyguards within palace grounds, by law enforcement to capture criminals (analogous to how Japanese police used chain weapons to entangle suspects), or by guerilla fighters who valued concealment. The relatively low lethality of moderate-weight meteor hammers is noteworthy – one scholarly comparison to Japanese chain weapons (manriki-gusari) noted they were often intended to stun or subdue rather than kill. In this sense, a meteor hammer could be seen as an early “non-lethal” option for lawkeepers (a blow that incapacitates rather than slays). Of course, heavier versions could be deadly, but they became harder to control and more predictable to dodge.

In summary, while rope darts and meteor hammers add color to the annals of weaponry, they were never pivotal in determining battles. Their presence in military treatises and literature shows they were acknowledged and occasionally used, but primarily by experts in specific situations. The image of a lone martial arts hero facing multiple foes with a whirling rope dart or meteor hammer lives more in legend and folklore than in regular military history.

Modern Usage and Revival

Martial Arts and Performance

In modern times, the rope dart and meteor hammer have experienced a renaissance as performance arts and sports. In the 20th century, as traditional martial arts were codified for competitions and demonstrations, these weapons were reintroduced for their spectacular visual appeal. Contemporary Wushu competitions include events for flexible weapons, and while the chain whip is more common, rope dart routines are also performed. Athletes use lighter darts and ropes, allowing for faster spins and safer practice. Sequences often involve dazzling acrobatics: the dart shooting under the performer’s leg, wrapping around their neck, then flying out to hit a distant target before recoiling. Such displays require immense skill and have helped keep the rope dart in the public eye.

Perhaps the most significant modern development is the incorporation of the rope dart into the global flow arts and circus performance community. Practitioners around the world now treat rope dart spinning as a form of dance and object manipulation. Starting in the 1980s, martial artists like Dennis Brown (the first African American to study in China’s Shaolin Temple) introduced rope dart techniques to Western students. By the early 2000s, a new generation began merging these techniques with poi spinning and fire dancing. Today, it’s common to see rope darts with soft heads (like beanbags or rubber balls) used for practice, as well as rope darts outfitted with LEDs or fire wicks for nighttime performances.

Performers wow audiences by tracing flaming or glowing arcs through the air, essentially turning the ancient weapon into a tool of artistic expression. This modern adaptation preserves the movements of the martial art while repurposing the intent—from combat to entertainment.

The meteor hammer, too, shows up in stunt shows and films, though it is less popular than the rope dart in the flow arts scene (likely due to its heavier, dual-weight design). Fire performers sometimes use a version of the meteor hammer (often called a “fire meteor”) with two burning heads, swinging it in patterns that produce circles of flame. Such performances often draw directly from traditional techniques, demonstrating how a weapon once used to strike enemies can be seamlessly turned into a form of fiery juggling.

A modern fire performance showcasing a rope-based weapon (fire meteor hammer or rope dart) uses kerosene-soaked wicks or LED heads instead of metal weights, bringing these ancient weapons to life as visual art.

Film, Television, and Gaming

Popular media has eagerly embraced these weapons for their dramatic potential. Kung fu cinema in particular has featured rope darts and meteor hammers in memorable scenes. In the Shaw Brothers film “Crippled Avengers” (1978), a villain famously wields a meteor hammer with deadly skill.

The weapon’s cinematic appeal also reached Hollywood and international audiences. Jet Li’s character improvises a meteor-hammer-like weapon (a firehose with a heavy nozzle) in “Romeo Must Die” (2000), and Jackie Chan comically uses a rope and horseshoe as a makeshift meteor hammer in “Shanghai Noon” (2000). Perhaps one of the most iconic rope weapon appearances is in “Kill Bill: Volume 1” (2003), where the schoolgirl assassin Gogo Yubari spins a modern meteor hammer (a chain with a spiked ball) in a frenetic battle.

More recently, the Marvel film “Shang-Chi” (2021) features a rope dart—Shang-Chi’s sister expertly wields a dart attached to a white rope, underscoring her martial prowess. These films, among others, have introduced the rope dart and meteor hammer to mainstream pop culture, often exaggerating their capabilities for effect, but undeniably sparking interest in their history.

Video games and anime have also popularized these arms. The character Scorpion from the Mortal Kombat franchise uses a chained dart as his signature weapon (a fantastical take on the rope dart), complete with the catchphrase “Get over here!” as he yanks opponents closer. In various Wuxia novels and TV series, heroes or villains armed with liuxing chuí or rope darts add flair to fight choreography. Such portrayals, while not always realistic, have helped ensure that new generations worldwide are aware of these ancient Chinese weapons. As a result, many martial arts schools today report students specifically asking to learn rope dart techniques after seeing them in media.

Sport and Community

Beyond entertainment, there is a growing community treating rope dart spinning almost like a sport or meditative practice. Enthusiasts exchange tutorials online, hold workshops at juggling and flow festivals, and even organize rope dart battles and games. Some have created standardized forms and competitions for rope dart, where practitioners are judged on difficulty and style of their techniques. This is a modern twist that likely never existed historically, effectively transforming the rope dart into a competitive artistic sport.

While the meteor hammer hasn’t reached the same level of community sport adoption, it is often included in discussions and demonstrations of historical weapons at martial arts conventions and cultural exhibitions.

In summary, the modern era has rescued the rope dart and meteor hammer from obscurity, reinventing them for performance and play. What were once weapons reserved for the few have become accessible to anyone with the patience to practice. This global revival underscores the fascination these weapons command—an interplay of danger, skill, and beauty that transcends their original violent purpose.

Notable Historical Mentions and References

-

Tang Dynasty Records (618–907 AD) – The rope dart is said to appear in writings from this period, marking its first known description. While the exact text is obscure, this indicates the rope dart concept existed by Tang times, likely under a general term for hidden projectiles.

-

Warring States Era Find (475–221 BC) – A bronze weight identified as an early meteor hammer was unearthed in Inner Mongolia (Ordos region) and is dated to the Warring States period. This artifact is one of the oldest physical pieces of evidence for rope-based weapons in China’s arsenal.

-

Classic Novel Water Margin (14th century) – Also known as Outlaws of the Marsh, this novel features at least two characters with rope weapons. Xue Yong wields a meteor hammer in the story, and Fan Rui uses a variant called the “Dark Meteor Hammer”, highlighting these weapons in Chinese literary tradition. These fictional accounts, based on Song Dynasty folklore, indicate that by the time of writing, such weapons were familiar to the audience.

-

Ming Dynasty Military Texts (16th–17th centuries) – The Wubei Zhi (武备志, 1621) includes illustrations of flexible weapons, showing devices akin to meteor hammers and flying claws meant to snare enemies. Another circa-1600 encyclopedia, San Cai Tu Hui, explicitly lists the “Star Hammer” (meteor hammer) among weapons. These references demonstrate official recognition of these weapons in military literature, if not widespread use.

-

Praying Mantis Manual (date uncertain, ~18th–19th century) – The Shaolin Praying Mantis boxing manual Yǐbō Zhēnchuán contains a diagram of a rope dart technique. This is a rare instance of a traditional martial arts text preserving rope dart knowledge, indicating its transmission in certain schools.

-

Qing Era Beijing Print (19th century) – A book on Beijing street vendors (c. 1800s) famously depicts a performer with a rope dart, with a bamboo tube handle on the rope. This is considered the first clear image of a rope dart as distinct from other rope weapons, highlighting its role in entertainment and martial arts demonstration at that time.

-

Modern Documentation (1980s–present) – Grandmaster Dennis Brown’s publications and teachings in the 1980s brought forward authentic rope dart methods to Western martial artists. In recent years, historians like Alexander Petty have written visual histories compiling ancient illustrations of rope darts and meteor hammers, and museums in China (e.g. Ordos Bronze Museum) have exhibited ancient meteor hammer relics. The continued research and writing ensure these weapons’ legacies are recorded for posterity.

Both the rope dart and meteor hammer occupy a special place in the tapestry of Chinese martial culture. From obscure beginnings and scattered mentions in old texts, they have traveled through folklore, been recorded in manuals, and finally emerged on the global stage as icons of martial arts. These flexible weapons illustrate the creativity of Chinese weaponry and the enduring fascination we have with the art of combat.

As historical artifacts, they tell of past warriors and performers; as cultural symbols, they continue to inspire awe and admiration in audiences and practitioners around the world.

Research Resource Link List

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meteor_hammer

https://fireandflow.co.nz/blogs/resources/the-low-down-on-dart

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rope_dart

https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202112/29/WS61cc30bb498e6a12c121c047/the-bronze-age-ordos-style-bronze-wares.html

https://www.reddit.com/r/ArmsandArmor/comments/d4mtxe/what_is_the_historical_origin_of_the_meteor/

https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202112/29/WS61cc30bb498e6a12c121c047/the-bronze-age-ordos-style-bronze-wares.html

https://theravenswoodacademy.squarespace.com/new-page-69

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/awdyvc/how_lethal_were_the_chinese_meteor_hammers/

https://pages.vassar.edu/barefoot-fireflies/rope-dart/

https://www.chinesesword.store/products/rope-dart-sheng-biao-stainless-steel/